Treatment of Pediatric Diaphyseal Femur Fractures Case Study

IntroductionIsolated pediatric femoral shaft fractures occur at an annual rate of 19 per 100,000 and represent the most frequent pediatric orthopaedic injury requiring hospitalization (1-2). The treatment of these fractures is dictated by various factors. The orthopaedic surgeon caring for these fractures must take into account the patients age, weight, family circumstances, and fracture pattern to determine the best treatment options. The cost for these various treatment options can also come into consideration (1-3).

The treatment options available for pediatric femoral diaphyseal fractures include: Pavlik harnessing, Spica casting, traction with subsequent casting, external fixation, intramedullary flexible or rigid nailing, and plating (locked and unlocked methods). The desire for early mobilization in order to allow for earlier return to school for the patient, decrease in the burden of home bound children on the families, and decrease the duration of hospitalization has prompted the use of surgical intervention over non-surgical interventions (3).

While the vast majority of pediatric femoral fractures will progress to union without complications, the advantages and disadvantages of the available treatments must be weighed carefully when determining the best option for each patient, particularly when considering patients that are on the borders of either weight or the general age groupings. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Pediatric Diaphyseal Femur Fractures provides the current evidence based guidelines to help guide the practioner when treating these injuries (4).

History and Physical

A 3-year-old male is brought into the trauma bay after being hit by a motor vehicle while he was walking on a sidewalk. His only complaint on arrival is of thigh and abdominal pain. He had no loss of consciousness. His triage vital signs are BP 96/68, HR 209, RR 30, O2 Saturation 99%, weight 15kg. The patient is treated as per advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocol by the general surgery trauma service with orthopaedic consultation.

On physical examination, he has superficial abrasions over the abdomen without peritoneal signs or deep tenderness. He has tenderness to palpation over the left upper thigh with soft compartments and intact pulses. The remainder of the physical exam is benign.

Imaging Studies

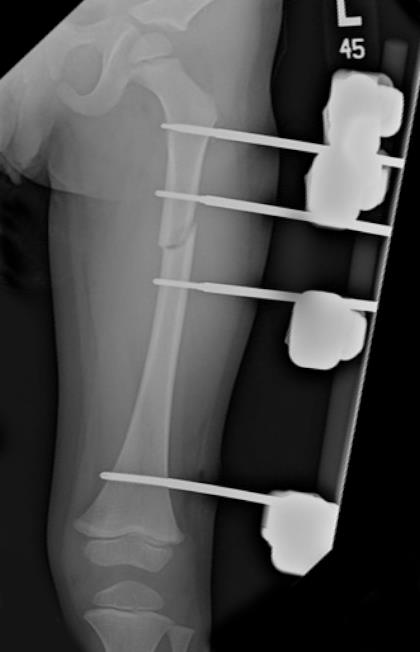

X-rays of the pelvis and left thigh as well as CT of the abdomen and pelvis reveal a left proximal third femur fracture with displacement and > 2cm of shortening, and a left pelvic wing subtle plastic deformity. Figure 1 shows the presentation x-ray. The soft tissues of the abdomen and pelvis on CT are negative.

Figure 1

Figure 1: AP radiograph of the pelvis and bilateral femora at presentation.

Treatment

The AAOS clinical guideline groups treatment of pediatric femur fractures into four categories based on age: 0 to 6 months treat with Pavlik harnessing, 6 months to 5 years treat with Spica casting, 5 years to 11 years treat with flexible nailing, 11 years to skeletal maturity treat with trochanteric entry rigid nail, plating or flexible nailing. Treatment is not solely based on the patient’s age, but should also consider patient’s weight, and family dynamics (4). Considering all of the treatment recommendations, a diaphyseal femur fracture with >2cm of shortening in the 6 months to 5 year age group has no supporting evidence. The amount of acceptable shortening remains controversial. No studies were identified in the literature specifically addressing whether spica casting should be utilized in this population or comparing spica casting with other treatment modalities.

The patient is admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit and placed in Buck’s traction pending definitive orthopaedic treatment. The following morning, the patient is deemed stable to undergo Spica casting of his left femur fracture. The Spica cast is applied without difficulty. During the afternoon on the day of cast application, the patient develops tachycardia and increasing abdominal pain that prompts a repeat abdominal CT scan. The repeat CT scan shows focal thickening and peritoneal enhancement with free fluid and air in the terminal ilium. At this point, the Spica cast is removed and he is taken to the OR by trauma surgery for exploratory laparotomy and is found to have a 1cm jejunal injury that requires repair along with an appendectomy. The patient is returned to the PICU for postoperative recovery and Bucks’ traction is reinitiated.

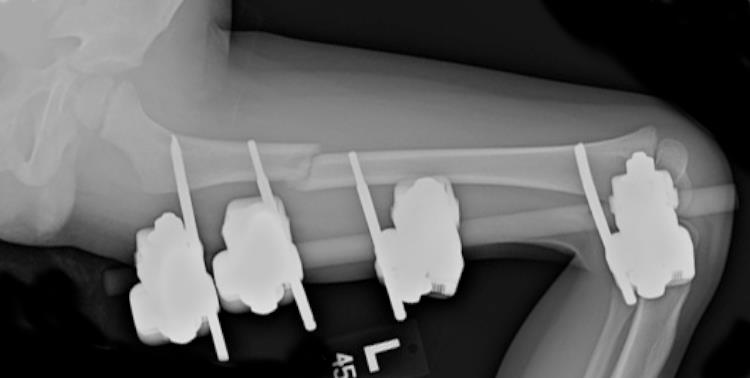

On the next hospital day, the patient is again cleared to return to the OR for femur fracture stabilization via external fixator (Figure 2). His pelvis is stable to exam under anesthesia. His hospital course is complicated by abdominal wound dehiscence requiring operative debridement and IV antibiotics. His pin sites and thigh remain benign during this time and the parents are instructed on pin site care, which is initiated on POD 6. He is discharged on POD 12 to home with follow up 1 week later in the orthopaedic clinic. He is discharged with a wheelchair for protected weight bearing.

Figure 2a

Figure 2a: AP radiograph

Figure 2b

Figure 2b: lateral radiograph after placement of the external fixator.

Post Hospitalization

The patient is seen in clinic one week after discharge without complaints. He has normal GI function. His pin sites are benign and x-rays demonstrate maintained alignment and interval callus formation. He is seen one month later and there are no problems. He is now walking on the leg. X-rays demonstrate sufficient callus present for ex-fix removal, which is performed that week. He was to follow-up post external fixator removal, but the family has not returned for follow-up. He has been seen in the primary care clinic since removal of the external fixator without leg complaints or documentation of significant leg length discrepency and is now almost 3 years out from injury.

Discussion

While the AAOS clinical practice guideline for the treatment of pediatric diaphyseal femur fractures outlines current evidence based treatment options, there remains a plea for additional scientific research in this area to improve the available recommendations. This case highlights a number of the management and treatment options for pediatric femur fractures.

First, higher energy injuries can result in additional bony and soft tissue injures not initially noted in early presentation. ATLS recommends secondary and tertiary evaluations to prevent missing these injuries. It is important to communicate this with families and to be cognitive and vigilant that they may exist. Appropriate and timely communications with families and other treating services has the potential to improve time to diagnosis and treatment.

In this situation, the initial decision to treat the child with the femur fracture was based on the age less than 5 years. However, with the evolution of peritoneal signs and persistent abnormal vitals, the initial treatment plan needed to be modified to be able to have access to the abdomen and still have bony stabilization. In children, as with adults, external fixators can provide initial stabilization as well as definitive treatment.

Spica casting remains an option for treatment of isolated femur fractures in children less than 5. Shortening and angulation can be accepted, as there remains extensive remodeling potential in this age group. The precise extent of allowable shortening or deformity remains unanswered. Open plating and flexible nailing, although less commonly performed in this age group, also remain options to the treating surgeon if dictated by the clinical scenario and are within the armamentarium of that treating surgeon’s expertise and training.

References:

1. Loder, R., Patrick W. O`Donnell, MD, PhD, and Judy R. Feinberg, PhD. Epidemiology and Mechanisms of Femur Fractures in Children. J Pediatr Orthop 2006;26:561-566.

2. Hinton, R., Andrew Lincoln, Michele Crockett, Paul Sponseller, Gordon Smith. Fractures of the Femoral Shaft in Children: Incidence, Mechanisms, and Sociodemographic Risk Factors*. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 1999 Apr;81(4):500-7

3. Flynn, John, MD. And Richard M. Schwend. Managament of Pediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2004; 12:347-349.

4. Treatment of Pediatric Diaphyseal Fractures Guidline and Evidence Report. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. June 2009.