Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture Case Study

The ruptured Achilles tendon is commonly seen in many orthopaedic practices. The AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline on Achilles tendon ruptures is a summary of the available literature designed to help guide the surgeon on management of these injuries. The following case presentation is designed to highlight how the Guideline can be helpful to the clinician in deciding the course of treatment.History

A 38-year-old man presents for evaluation of a left leg injury. Three days before presentation, he was playing basketball and felt a loud pop in his ankle. He turned around to see who had kicked him from behind, but no one was there. Because of the pain, swelling, and difficulty with ambulation, he presented to the emergency department the following day. He was splinted in the emergency department, given crutches, and referred to your office.

Physical Examination

The clinical history is consistent with an Achilles tendon rupture, but a thorough physical examination is performed to evaluate for concomitant injuries. No bony tenderness is appreciated, but there is a palpable defect in the Achilles tendon. Thompson testing is positive. The AAOS Guideline consensus recommendation is of at least two physical examination findings to establish the diagnosis of an Achilles rupture. (1) Thompson testing is found to have the highest sensitivity (0.96) and specificity (0.93) (Figure 1). (2) A palpable defect,with a sensitivity of 0.73 and specificity of 0.83, is a simple finding that can be easily identified. This test is very useful when a contralateral comparison is made (Figure 2). (3) Decreased ankle plantar flexion strength and increased ankle dorsiflexion are other valid tests, but they can be difficult to perform in the acute setting secondary to pain.

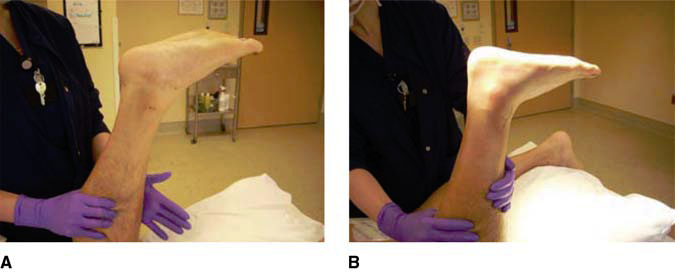

Figure 1

Negative Thompson test on the contralateral leg. Positive Thompson test on the injured leg.

Figure 2

Visible loss of Achilles definition on the left leg.

Imaging Studies

The physical examination did not demonstrate bony tenderness, so radiographs are not taken. Additionally, because the physical examination demonstrated two findings consistent with Achilles rupture, neither MRI nor ultrasonography was ordered. The AAOS Guideline recommendation for or against the routine use of MRI and ultrasound is inconclusive.

Treatment

The patient is diagnosed definitively with a ruptured Achilles tendon and is presented with both surgical and nonsurgical treatment options. Currently, the AAOS Guideline recommendations for surgical and nonsurgical management are both weak. The patient is counseled that nonsurgical management has shown satisfactory results, with lower complication rates. However, surgical repair has shown satisfactory results, as well, with studies showing a faster recovery time, quicker return to sports, and a lower rerupture rate compared with nonsurgical management.

The patient is counseled on the complications associated with surgical repair, with particular emphasis on wound complications and the subsequent management of these complications. The patient is a good surgical candidate because he is young, active, has no past medical history, and is not a smoker. The AAOS Guideline has a consensus recommendation that surgical management should be approached with caution in a patient with diabetes, neuropathy, an immunocompromised state, age >65 years, peripheral vascular disease, local/systemic dermatologic disorders, and/or who exhibits a sedentary lifestyle, uses tobacco, or is obese. With this information presented to the patient, he chose to go forward with surgical repair the following day.

Because of lack of literature/evidence, the AAOS Guideline has an inconclusive stance on preoperative immobilization or restricted weight bearing. The author schedules surgical repair within 1 to 4 days of presentation. Many patients with Achilles tendon rupture present to the office having been weightbearing for several days without immobilization. It is the author’s opinion that immobilization and restricted weight bearing are not necessary if the repair will be performed acutely. However, if the patient is having significant pain and is unable to bear weight, an equinus posterior splint is applied. Additionally, if surgery is delayed because of swelling, deep vein thrombosis, or other issues, the author prescribes immobilization and restricts weight bearing in an attempt to minimize retraction of the tendon.

Surgical Repair

Options for surgical repair include open, limited open, and percutaneous techniques. These techniques all carry a Weak strength of recommendation by the AAOS Guideline. An open Achilles repair was performed on the patient (Figure 3). Four strands of No. 2 FiberWire (Arthrex, Naples, FL) were used for a fourcore repair. It is the author’s opinion that a good closure of the paratenon over the Achilles tendon is important for an extra layer of protection in case of wound dehiscence and to avoid adhesions. The author performs a deep compartment fasciotomy to mobilize and allow easier closure of the paratenon. There is inconclusive evidence for the use of grafting or biologic adjuncts in the repair of acute Achilles tendon ruptures; it is the author’s opinion that these adjuncts are not necessary for a good result. The patient is placed into a bulky equinus cast and instructed to remain non–weight-bearing until the first postoperative visit, 7 to 10 days after surgery.

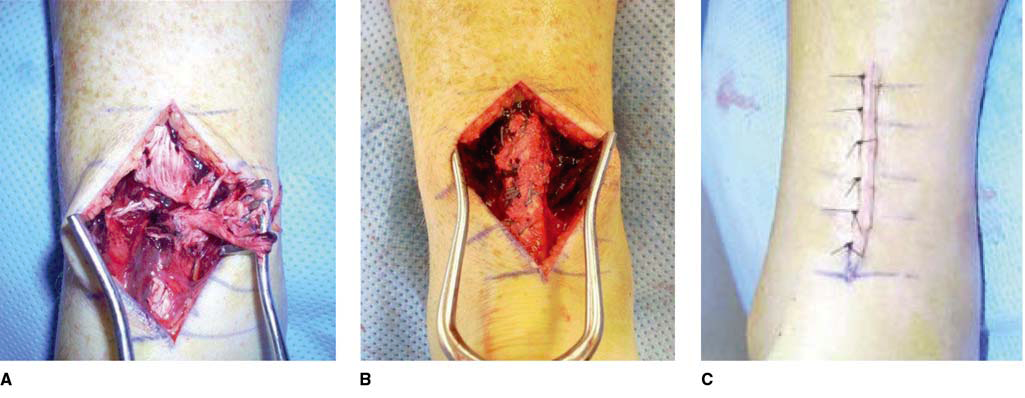

Figure 3

Ruptured Achilles tendon Completed Repair Wound Closure

Antithrombotic Treatment

Because of lack of evidence, the AAOS Guideline has an Inconclusive recommendation on the use of antithrombotic treatment. It is the author’s opinion that thromboembolic events after Achilles tendon repairs are of concern. However, the use of chemoprophylaxis is not without risk, either. The patient in this case was given the author’s routine protocol of 325 mg aspirin daily for the first 14 days after surgery.

Postoperative Protocol

The strongest recommendation that the AAOS Guideline has on Achilles tendon rupture management, a Moderate recommendation, is on a postoperative protocol that allows for early protected weight bearing and the use of a protective device that allows for mobilization. During the first postoperative visit, the cast is removed and the wound is inspected. If the incision is not healed or looks tenuous, the patient is recasted and returns for follow-up in 1 week. If the incision is healed, sutures are removed, and the patient is placed into a brace with removable

heel wedges. The patient is allowed to bear weight progressively as tolerated in the brace. After 3 weeks, the heel wedges in the brace are progressively removed over the course of 2 to 3 weeks. After 1 full week of ambulation in the brace with all wedges removed, the patient is allowed to begin ambulation without the brace.

Despite inconclusive evidence for physiotherapy after Achilles repair, the author routinely initiates its use once the brace is removed. Significant muscle atrophy and ankle stiffness from immobilization are addressed with physiotherapy.

The AAOS is unable to recommend a specific time by which patients can return to activities of daily living and athletic activity. The individual recovery process is extremely variable, and specific timelines to give patients can be unreliable. The author allows patients to initiate low-impact activities as tolerated once they are weaned off the brace. Patients are counseled that full recovery in terms of pain, swelling, and strength can take up to 1 year.

Based on the evidence available, the AAOS has set a Weak recommendation for allowing patients to return to sports 3 to 6 months after surgical repair of an Achilles rupture. The patient in this case returned to sports 6 months after repair.

Summary

Based on the evidence available, the AAOS recommendations on the management of Achilles tendon rupture range from Inconclusive to Moderate. Further studies are needed for stronger recommendations. However, knowledge of these guidelines is useful for the surgeon managing Achilles tendon ruptures and for counseling patients on treatment. It is the author’s opinion

that appropriate patient selection and meticulous soft-tissue technique are important for a good surgical outcome.