Optimizing the Management of Rotator Cuff Problems Guideline Case Study

IntroductionRotator cuff disease is perhaps the most common shoulder problem treated by orthopaedic surgeons. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) Clinical Practice Guideline, “Optimizing the Management of Rotator Cuff Problems,” is a summary of the available literature designed to help physicians manage this condition. The following hypothetical case presentation highlights how these guidelines can help the clinician in deciding the course of treatment of patients with a rotator cuff problem.

History

A 55-year-old, right-hand-dominant man presents to an outside orthopaedic surgeon after a fall approximately 9 months earlier. The patient reports he slipped and fell on ice, had no preceding antecedent shoulder pain, and had immediate onset of pain after the fall. He states that his pain level has improved from 9 (of a maximum of 10) to approximately 4 on a visual analog scale. He reports night pain in the lateral arm distribution that is intermittent. Otherwise, he is in good overall health and works as a pilot.

Physical Examination

The patient can actively elevate his arm to approximately 150° in the scapular plane, which is approximately 15° less than on the contralateral side. He has no obvious atrophy of the supraspinatus or infraspinatus fossa. He has full passive motion in his right shoulder, comparable to that of the uninjured shoulder. Rotator cuff testing is significant for weakness and pain with thumbs-down forward elevation in the scapular plane, but there is good strength in external rotation at the side as well as a negative liftoff test.

Imaging Studies

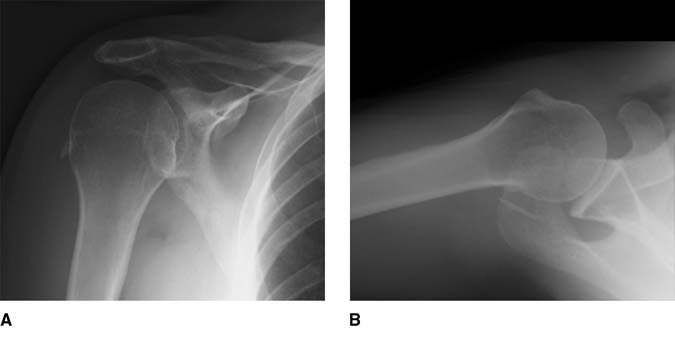

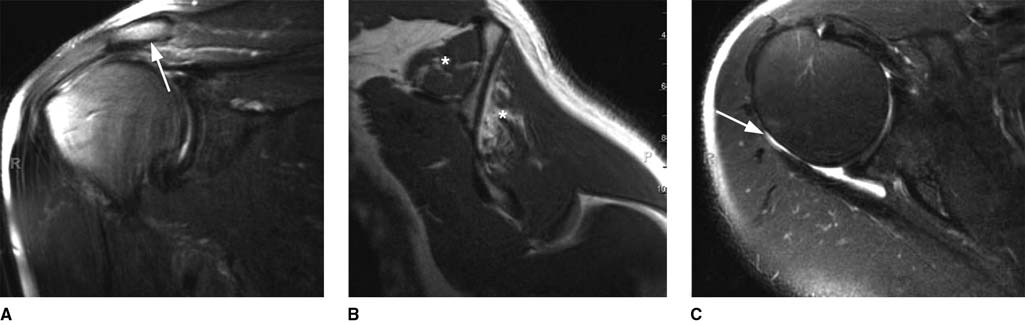

Plain radiographs of the shoulder are significant for slight calcification near the posterior aspect of the greater tuberosity (Figure 1). The shoulder is well centered, with no humeral head elevation and no glenohumeral or acromioclavicular arthritis. MRI of the shoulder is significant for a full-thickness tear of the supraspinatus retracted to the mid humeral head. There is no significant fatty degeneration or atrophy of the rotator cuff muscles even though the image was obtained 9 months after an acute traumatic injury. The infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis are not involved with the tear (Figure 2).

Figure 1

AP (A) and axillary lateral (B) radiographs demonstrating a concentrically reduced joint with slight posterior calcification near the greater tuberosity but otherwise no arthritic changes.

Figure 2

Coronal (A and B) and sagittal (C) magnetic resonance images demonstrating a rotator cuff tear involving the supraspinatus muscle (A and B), with retraction to the mid humeral head, yet with minimal fatty degeneration or atrophy of the supraspinatus (C). * = supraspinatus muscle

Treatment

The patient is counseled regarding his treatment options by the outside orthopaedic surgeon, including nonsurgical management with pain and anti-inflammatory medications, cortisone injections, and physical therapy, as well as surgical treatment with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. His tear, which was originally acute, has become chronic. The patient elects to proceed with nonsurgical treatment, including a cortisone injection, use of anti-inflammatory medications, and physical therapy. The patient improves to the point that he has only some mild nagging pain but no night pain and no difficulties with his job.

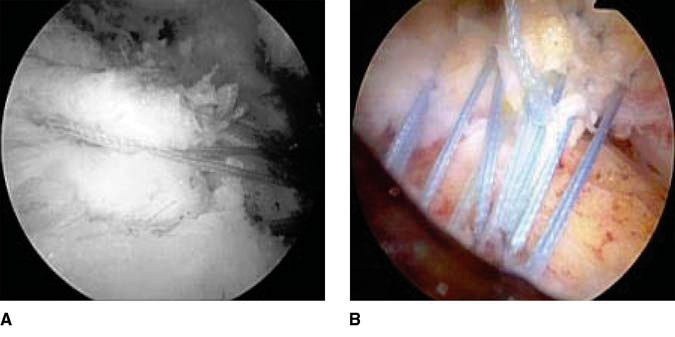

Approximately 3 years later, the patient presents to us with an insidious onset of worsening shoulder pain. He does not report any further episodes of trauma. On physical examination, he is able to elevate his arm actively in the scapular plane to 140°. He has weakness in elevation in the scapular plane as well as with external rotation at the side, suggesting weakness of both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, respectively. MRI of the shoulder confirms enlargement of the tear involving the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, as well as fatty degeneration of both muscles (Figure 3). The patient elects to undergo arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Despite the progression of tear size, it is found at the time of surgery to be reparable (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Coronal (A), sagittal (B), and axial (C) magnetic resonance images demonstrating enlargement of the tear involving both the supraspinatus (A, arrow) and infraspinatus (C, arrow) tendons, with significant fatty degeneration (*) of both muscles (B).

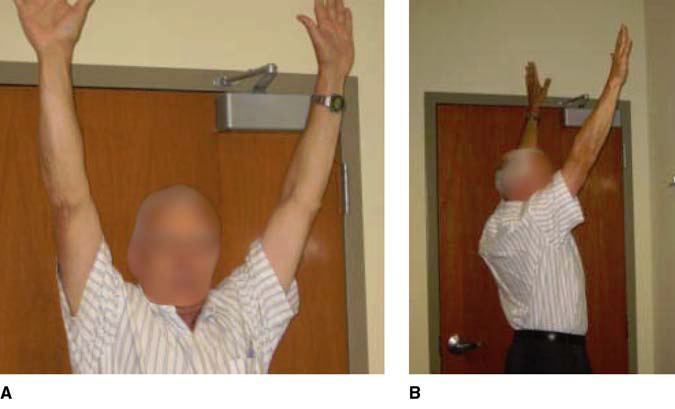

Figure 4

A and B, Arthroscopic images of a complete arthroscopic repair of chronic supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon tears.

Outcome and Resolution

The patient significantly improved after surgical treatment, with resolution of his pain despite some persistent strength deficits (Figure 5). Chronic changes to the rotator cuff muscles, including fatty degeneration and atrophy, often result in some strength deficits because these changes are irreversible, even when a rotator cuff repair heals. Similarly, these chronic changes predispose patients to worse healing after a repair.

Originally, the patient elected to proceed with nonsurgical treatment of his full-thickness tear. At the time of his initial presentation to the outside surgeon, his acute traumatic tear had already become chronic because of the 9-month delay. Knowledge of the natural history of chronic rotator cuff tears indicates that there was a strong chance that this tear would progress over time, and the patient’s tear did progress from 9 months postinjury to 3 years postinjury, leaving him with a larger tear as well as permanent muscle changes. Although this course of treatment did not preclude surgical repair, it is likely that this delay did affect the outcome of his eventual surgical treatment with regard to improvement in strength.

Based on the AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline, “Optimizing the Management of Rotator Cuff Problems,” early surgical repair of an acute full-thickness rotator cuff tear is an option. The AAOS was able to make this recommendation even though the strength of the recommendation is weak because it is based on only five level IV studies. In this case example, if the patient had originally presented after his injury instead of waiting 9 months, recommending early surgical repair would have been in line with the AAOS guideline. Because the patient did not present initially and did not undergo immediate repair, his results reflected the data, suggesting later repairs can have an effect on final strength.

When the patient finally presented for treatment, his once acute tear had become chronic because of the 9-month delay in presentation. At that time, he was counseled regarding surgical and nonsurgical management. After counseling by the outside orthopaedic surgeon, he elected to undergo physical therapy and have a cortisone injection. Based on the AAOS guideline, a recommendation could not be made for or against the use of physical therapy or a cortisone injection in patients with chronic rotator cuff tears. This recommendation was graded inconclusive because no data supported a definitive positive impact of physical therapy, and there was no evidence of significant adverse effects of this treatment. Similarly, there was weak and conflicting evidence to support the use of corticosteroids in the setting of full-thickness rotator cuff tears.

When the patient presented with recurrent symptoms, he was again offered the option of surgical treatment, based on the guideline, with expectations of pain relief and functional improvement despite the presence of some muscle deterioration. Based on the AAOS guidelines, rotator cuff repair is an option for patients with chronic, symptomatic, full-thickness tears. This recommendation was graded as weak because it is addressed by one level III and multiple level IV studies. The patient’s outcome reflected the data that, even in the presence of muscle changes, pain relief and functional improvement are reliable.

This patient was counseled that, because of muscle quality at the final time of repair, healing and outcome could be inferior compared with the outcome of surgical repair that might have been expected had treatment been undertaken acutely, when there was no muscle dysfunction. Based on the AAOS guidelines, it is an option or physicians to advise patients that MRI tear characteristics of the rotator cuff muscles, including fatty degeneration and muscle atrophy, correlate with less favorable outcomes after rotator cuff repair. This recommendation was graded as weak because it was addressed by six level IV studies. The data supporting this recommendation suggest that preoperative fatty degeneration of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus predisposes patients to worse healing and worse functional outcomes. Although a postoperative ultrasound was not performed in this patient to document healing, his outcome was likely influenced by the muscle changes, given his residual postoperative weakness.

Based on the evidence available, the AAOS recommendations on the management of rotator cuff problems range from inconclusive to moderate. Knowledge of these guidelines is useful for the surgeon in managing rotator cuff problems and for counseling patients on their treatment. This case study underscores several of the higher graded recommendations.

Unfortunately, one of the most important findings of these guidelines is the relative lack of quality, high-level research. This is consistent with multiple controversies surrounding rotator cuff disease as well as with the wide variation seen in treatment. This evidence-based process underscores the strong need for quality evidence and further research that orthopaedic surgeons can rely on to provide clinical care to patients with rotator cuff disease.

Figure 5

A and B, Clinical postoperative photographs of a 55-year-old man demonstrating forward elevation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.